Hope For Hiatt Street

Reporting by Nancy McLaughlin & Kenneth Ferriera

Photos by Kenneth Ferriera

Sandra Abarca plays with her daughter Elisa Chan while sitting at the family dining room table at their home in the Jamison Mobile Home Park on Sept. 16.

The streetlights were flickering on by the time Francine Munoz-González got back from the park with her younger siblings and noticed her mother standing along the row of aging mobile homes talking excitedly in Spanish to one of the neighbors.

"I thought they were having an adult conversation," the high school senior said of not bothering to linger before going up the wooden steps and inside their blue and white single-wide with her sister and two brothers.

Sandra Abarca prepares a meal of enchiladas verdes for her family's dinner at her home at Jamison Mobile Home Park on Sept. 17. Abarca found out about the sale when a neighbor went to pay her rent in July and learned that a developer had a contract on the property. By that time, Abarca and Josue Chan had already completed the paperwork to enroll their children in school. "We were very sad because we were just starting to get settled in," Abarca said. "We made this our home."

Then her mother, who can speak English, but has trouble at times with words and context, came for her — with urgency.

"We walked to Mr. Randy's house," Francine said of a memory that still puts a quiver in her voice. That's "Randy" as in Randy Williams, another neighbor in the mostly Hispanic mobile home park. He had talked to the landlord, but he didn't speak Spanish like most of the other neighbors.

"She's, like, 'Is it true they are kicking us out?'" recalled Francine, who, until that point was clueless as to what was bothering her mother. "And I'm, like, 'What?'"

Everyone has a different view of the 3 acres of land up for sale on this short stretch of Hiatt Street in the shadow of UNCG.

It's financial opportunity for the family whose ownership goes back three generations.

It's an investment for Owls Roost Properties, a Greensboro developer with a good reputation and successful apartment complexes already in its portfolio.

And it's home for people like Munoz-González, Williams and a handful of other tenants, most of whom have lived there for decades paying monthly lot rents.

Meily Molina, whose youngest child is 2, has lived in the park for 14 years and used public transportation for chemotherapy appointments while battling cancer.

Margaret Morales, on disability, put a mobile home on a lot 32 years ago.

The Garcías down the street just welcomed a baby.

Life here had been quiet up until recently.

Now, this small parcel that holds the Jamison Mobile Home Park is at the epicenter of a fight between groups who think their claim on the land is equally valid.

The mobile home park, which on most nights is set to a soundtrack of passing trains and children at play, is a place few probably know exists.

With the land's estimated value of about $350,000, the maze of homes is couched between an apartment complex on one side and an abandoned building with broken windows on the other. Nearby train tracks run past a Sherwin Williams plant down the street, framing the area squarely in urban life.

Welcome to a lesser known corner of Greensboro and the Lindley Park neighborhood.

Rays of light filter through the trees as the sun sets behind the Jamison Mobile Home Park on Sept. 23, along Hiatt Street in Greensboro.

Dreams are in the soil here. Blood, sweat and tears. Aspirations. The expectations to be in this community — as retired civil rights attorney Lewis Pitts has said — are what's being ripped apart for the 18 families calling it home when the sale of the land was announced months ago to make way for a new apartment complex.

Once among the cheapest, if not the cheapest, rent in the city, the $315 tenants pay each month secured the lots for the next month. That hadn't been a problem for them until July, when word began to spread that they would have to be out in two months. Moving a mobile home — if it's able to be moved — can cost thousands of dollars for residents already struggling to make the rent.

The July 12 letter from Family Properties gave tenants who owned their homes 75 days to move. Renters had to be out by Aug. 30. Security deposits, less than the current rent, would be accepted as the last month's rent.

"We will be turning off the utilities by Sept. 31," read the letter bearing park manager Lynne Anderson's name.

It went on to say the Jamison Park community would be missed.

Through an attorney, developer Owls Roost Properties has said that questions should be directed to Family Properties, because the sale hasn't been completed.

For their part, Owls Roost found a property up for sale, looked at the viability of building there, and made an offer.

"We were not aware that there was any issue with current residents at the property," said Marc Isaacson, an attorney representing the company.

Grandfathered in despite ordinances at times outlawing new mobile home parks in the city, the address had made Jamison residents beneficiaries of good schools, a location near downtown, nearby public transportation and put them within walking distance to a university and the Greensboro Coliseum.

The city around them — like others across the country — has suffered a net loss of affordable housing over the years, in part, because apartments and free-standing homes being built have been getting more expensive.

The Jamison park was a value even by affordable housing standards.

These are working-class people. If displaced, there may not be a place for them to go in a city already struggling to meet the needs of so many others like them.

Jamison tenants complain about getting the first notices written in English when Spanish is their first language. Some say they were asked to tell other neighbors.

A further snub, tenants say, is how they were expected to quickly pack up and move. As if they didn't matter.

Valeria Medina Lara (left) plays in the front yard as her parents Brenda Vanesa Para Mosquda (center) and Miguel Angel Medina Garcia prepare to take a portrait in front of their home at the Jamison Mobile Home Park on Hiatt Street in Greensboro on Oct. 2.

Their plight reached Siembra, a grassroots group for immigrant rights, which has helped residents to organize and make an attempt to buy the land themselves.

Margaret Morales, a 66-year-old who lives alone and is on disability, has decided to leave.

"This is not the greatest place in the world, honey, but I’ve lived here a total of 32 years," she said. "I’ve always felt that living alone, especially, I’ve always felt OK. I’ve always felt like the neighbors watched out for me, and they do."

She spent tens of thousands of dollars, awarded as part of a settlement of a lawsuit, on renovations in 2017.

"I put it into this place," Morales said." I put it into this home. I had to fix quite a number of things for it to be livable — hopefully for life."

Community members meet after work on Oct. 1 to plan events to help raise awareness and money for their battle against a developer at the Jamison Mobile Home Park in Greensboro.

In the meantime, the "Jamison" sign at the entrance to the mobile home park has since disappeared.

So, too, have mobile homes owned and rented out by Shirley Todd Jamison, a nurse, missionary and part-owner of the business, whose death in 2017 led her family to put the land on the market.

Anderson, who is one of the executors of her aunt's estate, also manages the mobile home park.

Anderson — who didn't respond to requests for an interview — said in August, after tenants took to the streets in protest, her aunt stipulated in her will that the property be sold and the proceeds divided among her grandchildren. Shirley Jamison did not have children, but she left stocks and bonds and even her 1999 Toyota Camry to her sister Sara's grandchildren.

At that August protest, Anderson stressed she wasn't trying to make Jamison tenants homeless.

Still, homeless is what some of them may become.

****

Francisca González-Sánchez remembers walking along Hiatt Street nearly 20 years ago with husband Rafael and spotting the mobile home for sale.

Her OB-GYN had told her to slow down and stop working with just over two months to go before the birth of her first child. But that would also mean losing nearly half the family's income.

The couple had first met in elementary school back in their native Mexico and reconnected as adults in North Carolina.

González-Sánchez takes a certain pride in tracing a work history that starts with the $6.50-an-hour job at McDonald's. She would move up to $8-an- hour in housekeeping at the Grandover resort — a job she kept for 14 years.

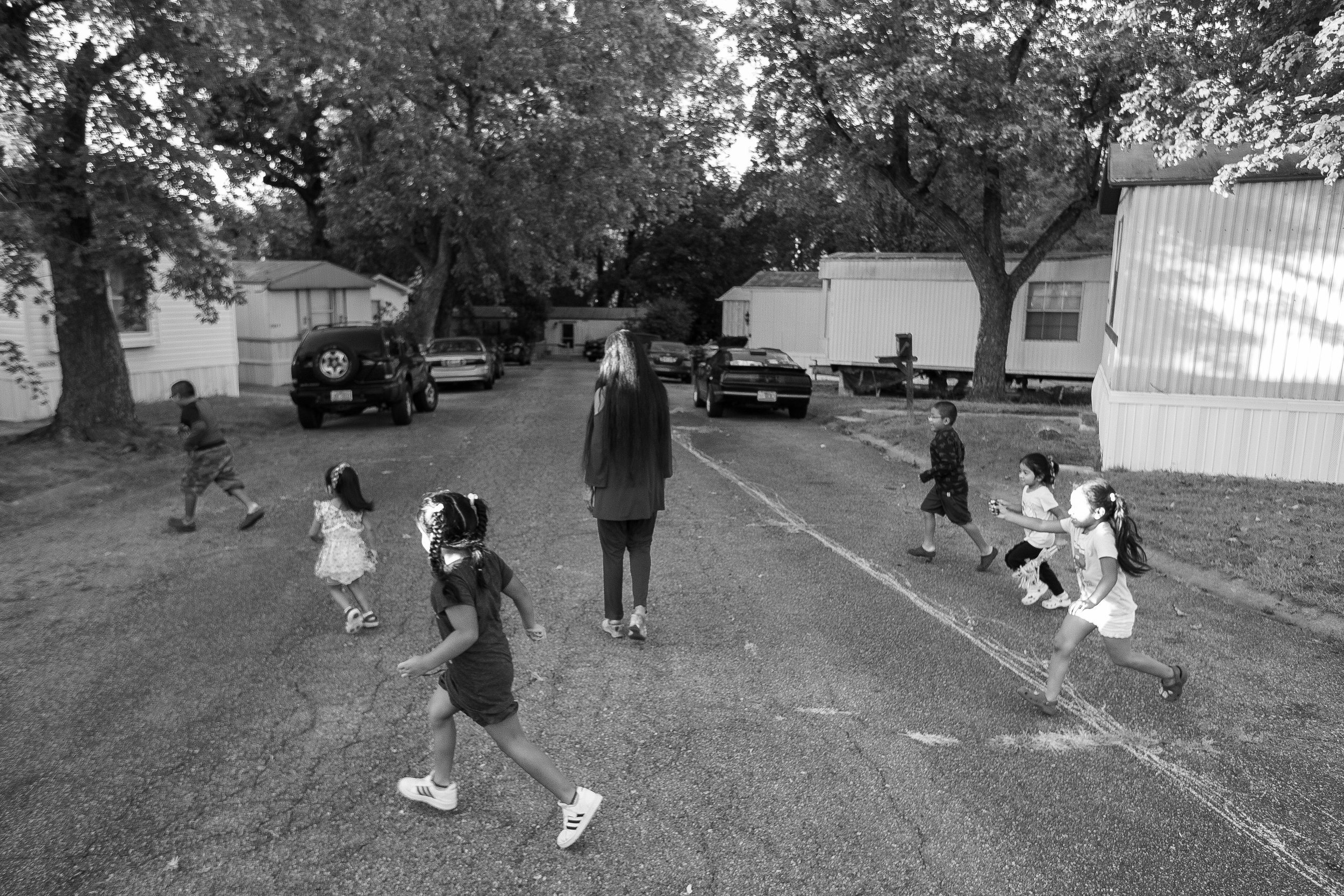

Neighborhood children play in an empty trailer lot that remained vacant after former residents moved out, on Oct. 31

Later, she and Rafael would try their hands at running a food truck.

"You feel good about owning something," she explained, running her spoon through a bowl of soup as she took a seat at the kitchen table in her small, but tidy, mobile home. "In the same moment, I don't feel good because the kids are spending more time in day care. They say, 'Mom, I don't see you. We don't eat together.' They told me, 'We miss you,' and it broke my heart."

The couple later found jobs at Proctor & Gamble and then Gilbarco.

Back when she was pregnant with Francine and was out of work, the couple had to leave a $700-a-month rental home off Merritt Drive for a $400-a-month duplex they thought they could afford near Hiatt Street in hopes of saving money. But that first month, the utilities ate away the savings they expected.

At Jamison Mobile Home Park, they were able to work out a deal where instead of just renting the unit, they were able to purchase it from the family who owned it.

"It was less stressful," González-Sánchez said. "We could buy stuff for our children. I wanted my children to have opportunities I did not have."

When they looked at other housing in the area recently, they discovered it was out of their price range.

So staying at the mobile home park seems like their only option.

González-Sánchez said: "My neighbor says, 'We are 18 or 19 families living here. We can try to buy it."

They began to draft a letter.

Francine, who is applying to Duke and UNC-Chapel Hill, recently found her mother reading a book about Native Americans and the history of America.

And the older woman was taking notes.

While asking the owners of the mobile home park for the opportunity to buy the plot of land, she and her husband scouted out neighborhoods and started knocking on doors, asking homeowners if they needed their grass cut as a way of raising extra cash.

"I have always respected my mother," Francine said, "but I see her even more as a leader."

****

Francisca Gonzalez Sanchez helps her son David Munoz-Gonzalez get ready for the school day with a shower at their home in the Jamison Mobile Home Park on Nov. 1.

The next street over, at the home of Sandra Abarca and Josue Chan, the older children are finishing homework and the younger ones are playing with Barbie dolls. Abarca's sister lives down the street, and the couple purchased the older mobile home, which needed a lot of work, a year ago so their children — now on the couch and floor — could grow up together.

Chan remodeled the whole unit, including replacing a floor that was falling apart. He remembers asking Anderson, the park manager, if he could build a storage unit on the property.

She turned him down.

"I asked the lady why," he said through an interpreter in August. "She responded to me: 'You never know.' I was left thinking about that."

Evelin Hernandez peeks over the arm of a couch to watch a video with Elisa Chan on an iPad at their home in Jamison Mobile Home Park on Sept. 16 in Greensboro.

They found out when a neighbor went to pay her rent in July that a developer had a contract on the property. By that time, Abarca and Chan had already completed the paperwork to enroll their children in school.

"We were very sad because we were just starting to get settled in," Abarca said. "We made this our home."

In a panic, they started calling area mobile home parks and realized that there was nothing available for them.

They faced the possibility of moving out of the city.

"That would be the only option and that's what we don't want," Chan said. "If the lady wants to sell it, we want to buy it."

It was worth asking. It's unclear how much Owls Roost has offered for the property. The families have also stopped by the company's office to set up a meeting with officials. Some among them are hoping that public pressure might result in the company backing away from the deal.

"Perhaps our voice doesn't have a lot of weight," Chan said as summer turned to fall, "but we believe we are going to achieve something."

In August, the Jamison tenants showed up in matching green shirts bearing the words "Hiatt Street" as they gathered at the Battleground Avenue address of Family Properties to present a letter asking to buy the land.

Setting up in an adjacent parking lot, they rallied with supporters as Anderson asked them to leave. The sea of people included advocates for immigrants and affordable housing, their Lindley Park neighbors and others.

"I implore you," someone from the crowd directed Anderson's way, "to do what is good."

Sandra Abarca, Evelin Hernandez, Ariana Hernandez, Elisa Chan, and Analia Chan (from left) take a break from playing to eat snacks in the back of a van at the Jamison Mobile Home Park on Sept. 23.

Anderson, phone in hand, said she was waiting for the police.

"We are not trying to make them homeless," she said to those around her under the blistering sun. "We are not doing anything illegal."

There was the sound of both anger and anguish as Anderson lamented the scene around her.

"They have the right to free speech," Anderson said as police arrived, "but this is wrong."

In her hand were letters offering an extension to stay another 90 days. She tried passing them out, but there were no takers.

"They are trying to force our sale not to go through," she said with a hint of exasperation. "None of them have asked why we are selling the park."

The deed of the property, a former landscape nursery, bore the name of Shirley Jamison's parents in 1948. By 1975, it was in the names of their daughters, Shirley and Sara.

Shirley, who died in April 2017, spent 39 years in Costa Rica and Colombia as a missionary and nurse.

Sara, who died months after Shirley in 2017, and her husband moved to Afghanistan to teach physics and math at a college there. They eventually moved back to the United States. When their six children were grown, they moved to Pakistan where they taught English as a second language to Afghan refugees.

By 1995, the mobile home park had been deeded solely to Shirley Jamison.

But by 2004, she only had a third interest in the property, along with two of Sara's children: Lynne Anderson and Rebecca Duhan.

Anderson said her aunt stipulated in her will that the property be sold and the proceeds divided among young heirs.

And on that August day, the Jamison tenants were hindering those plans.

Children look out the window of their mobile home during a festival on Oct. 31 to raise awareness and money for the owners of mobile homes at the Jamison Mobile Home Park.

****

The weariness is starting to show.

Francine has tried separating her home life from school, where there are band practices and sports. Filling out college applications. The challenges being in the International Baccalaureate honors program.

One day at cross country practice, it all came out.

Margaret Morales poses for a portrait on the hood of her 1979 Pontiac Trans AM outside of her home Oct. 2 at the Jamison Mobile Home Park on Hiatt Street in Greensboro. Morales, who lives on disability, put a mobile home on a lot 32 years ago. The family that owns the land the mobile home lots sit on has decided to sell the property to a Greensboro developer.

"I had been holding it all in," she said, sitting quietly in early November in a bedroom that's covered in pictures of her siblings and adorned with dolls from childhood that her grandmother had given her.

"I was confused, heartbroken," Francine explained. "I've lived here my whole life. This is where I’ve grown up. It’s made me the person I am now."

That day, she fell behind the other runners and told the coach she was having cramps.

Her sister had been suffering from anxiety attacks ever since she heard the news.

"It’s like a shadow over me — just always," Francine said. "I find joy in doing what I love to do, but I never stop thinking about what’s going on at home."

Recently, she was surprised to receive the coach's award for cross country and was inducted into the National Honor Society, as her parents and siblings watched.

"I try to enjoy everything and I’m always smiling," Francine said, "but it’s bittersweet."

The neighbors tried their luck attending a meeting of the City Council, where Francine was among speakers, urging elected leaders to do something.

Council members were sympathetic, but they offered no easy answers.

In the days after that meeting, local experts in law and housing met with Jamison residents to brainstorm options. Again, there were no easy answers.

The ages of some of the mobile homes make it unlikely they can be physically moved. If their owners are displaced by the property's sale, they will literally have to be left behind.

"Somebody owns their mobile home for 20 years and now is going to have to walk away from it," said Beth McKee-Huger, the former executive director of the Greensboro Housing Coalition. "It’s just heartbreaking to be in such a situation."

A block party in late October that featured food cooked by Jamison residents and a mariachi band raised $13,000.

And fueled their hope.

Some of the neighbors are already leaving.

"I felt at first as if I were abandoning them," Randy Williams says from the hotel room he and his wife have called home for the last two weeks, "but I had to look at it realistically."

At least four other families are now in various stages of leaving.

Williams had been a part of the protest in front of Family Properties. Now, he sits with his wife in the hotel room, waiting as their mobile home is relocated to a new place just outside the city limits.

Rafael Munoz-González peeks out the kitchen window while his mother prepares dinner at the Jamison Mobile Home Park on Hiatt Street in Greensboro on Sept. 17.

Another Jamison family will be waiting for them when they get there.

The college sweethearts — she's from Greensboro and he moved here from Arkansas as a college freshman — are bracing for the change in community and camaraderie.

"I’m 68 years old and I’ve lived many places, and these are the best neighbors I’ve ever had," Williams said.

Williams moved into a home already on the lot that he purchased from a friend in 1999.

His son, now in the Air Force and stationed in Idaho, lived there for much of his life.

"Our community ... everybody waves, everybody smiles — well, there are a few that just wave," he said, with a momentary laugh. "I think it's a shame that this has to go."

He, too, was upset when the letter came announcing the sale.

"Our landlords own this land, and they certainly have the right to sell it," Williams said. "Certainly, we should have been given lots of time. The owners knew that."

It bothers him how an eventual extension, allowing the families to stay past Christmas, was offered as a gift to residents.

"The way they framed it was that they were granting us the extra time," he said.

But North Carolina statutes require that tenants of mobile home parks which are being repurposed have at least six months to vacate the premises.

"They had to do that," Williams said.

He knows he's one of the lucky ones. He found somewhere to go.

Williams had to take out a bank loan to come up with the thousands in moving expenses.

"It put me in debt significantly," Williams said.

But then, he had no choice.

"There are some who are still clinging to the idea that the park could be sold to them," Williams said, "and to me it’s a very unrealistic thing."

Margaret Morales walks back to her home while children play in the street at the Jamison Mobile Home Park on Hiatt Street in Greensboro on Sept. 23. The ages of some of the mobile homes make it unlikely they can be physically moved.